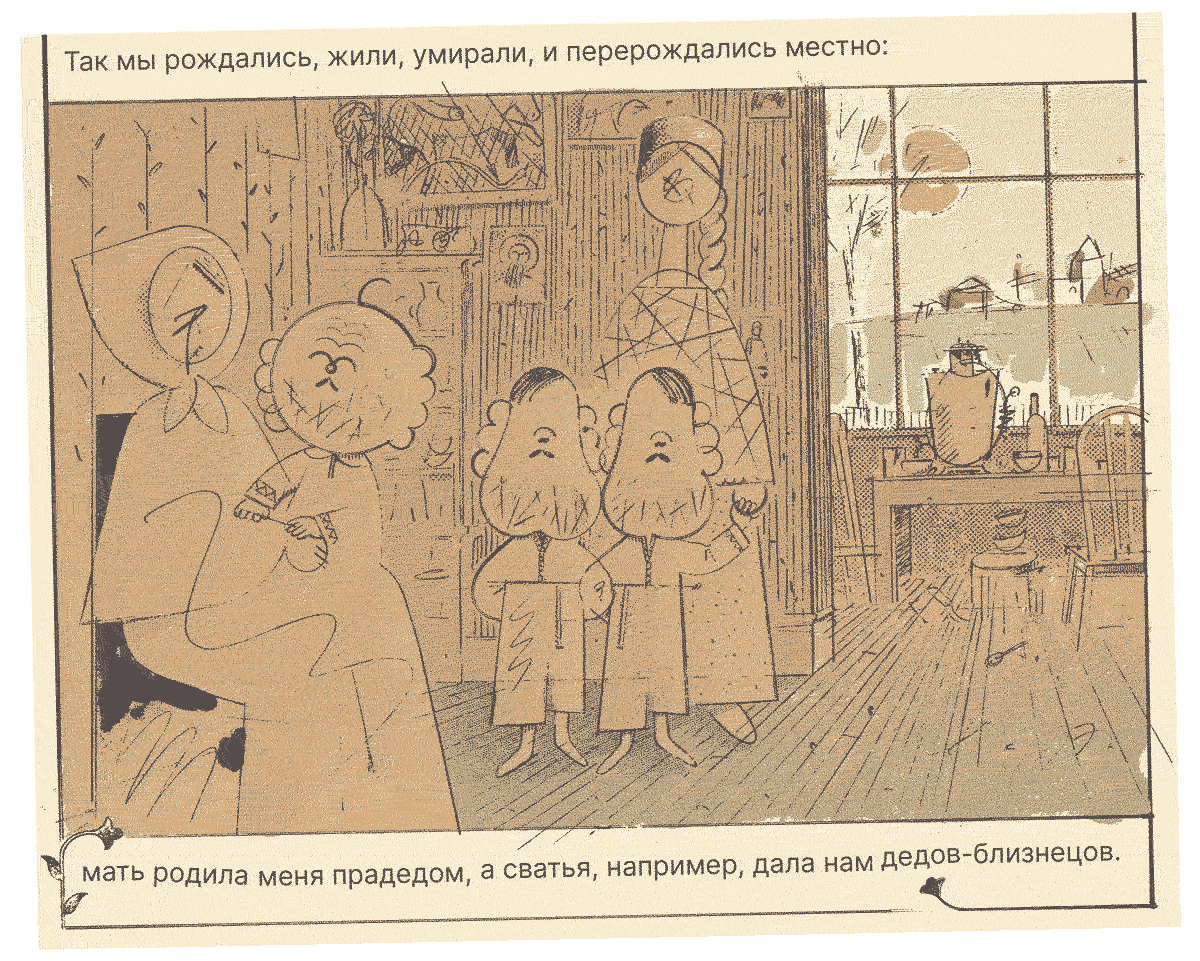

This month I finished a short dense comic for Russian Esquire magazine, which has been renamed to Rules for Living (not making this up). It’s proving to be a bit of a challenge to translate, so meanwhile enjoy some dumb cartoons—been drawing them in the morning as soon as I wake up, just putting in whatever pops into my head.

And if you want more, sign up for my paywalled second newsletter, so you can find out all the hot goss about the Midwestern Cartoonists. Again, if you don’t want to spend money on it, just drop me a line and I’ll put you on a list, no worries! Only support if you feel like it.

And here’s the second (and probably penultimate) part of my Unified Theory of the Funny. If you missed the now-classical first part, it’s in the last month’s newsletter.

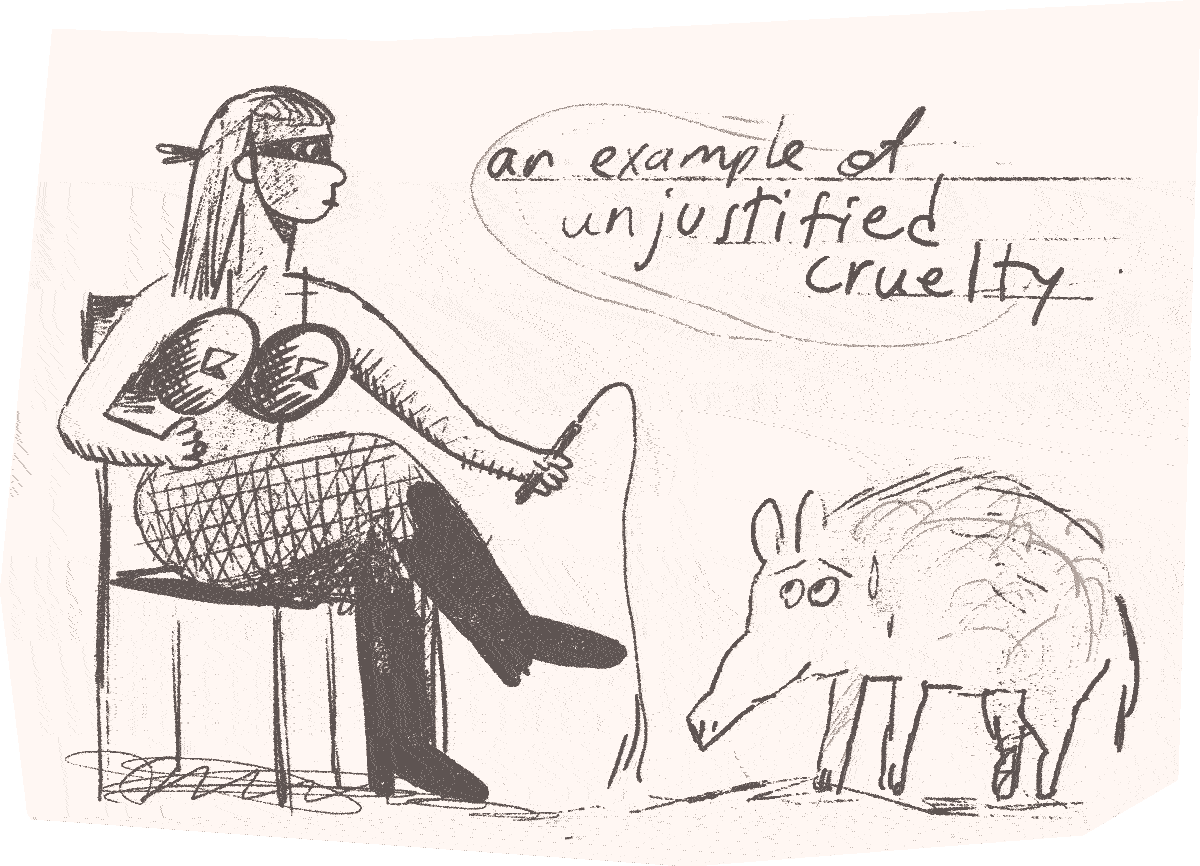

First of all: I’m a highly sensitive little man, and at home all I need is love, safety and cats. In fiction, however, it’s all despair, danger and cats (they are eternal and omnipresent). I’ve been thinking about this disconnection a lot lately, how much good character comedy relies on cruelty, or at least uses it as foundation. Here I’m talking specifically about narrative comedy centered around interpersonal relationships—elsewhere there’s plenty of great humor that isn’t cruel, so don’t go on twitter saying that I want everyone to suffer (I do, but that’s beside the point). The mechanics of cruelty, however, are as complicated as anything else, and, unlike the more absurd stuff, cruelty runs the risk of spiraling into callousness and offense. The latter of course is a very subjective quality, and for the purposes of this demonstration, I’m going to set morality aside, and treat cruelty as a narrative device.

The way I see it, ‘good’ cruelty is like a bouncy castle, where characters can be tossed around without consequences. We find relief in this kind of comedy because it lets us play out our darkest anxieties without subjecting ourselves and others to the effects. It’s no wonder that some of the darkest stuff has been written by very normal people living orderly lives (J.G.Ballard is a perfect example of the Flaubert dictum (be regular in life in order to be violent in art) taken to the extreme).

I think cruelty works when the author first establishes the rules and boundaries of their world, then proceeds to stretch these boundaries, carefully. So, even though the first few seasons of Peep Show are somewhat uneven in tone, the general dynamic is set, and remains consistent through the whole run. Transgressions are approached carefully and with some preparation, and this way we have memorable moments of deep discomfort that feel natural, but not natural enough to be disturbing. Enough is rooted in reality, enough is edited and paced out. There is however one episode that stands out and stretches the boundaries quite a bit, and I will examine it in greater detail a few paragraphs onwards. That aside, the roles and relationships remain fairly consistent, and through the seasons, our growing familiarity reinforces the bouncy castle, allowing the creators to torture their characters as violently as they like.

Still, some of my favorite stories are the ones that have bizarre tone shifts. There’s quite a lot of it in Korean cinema, it seems, and my favorite example is Barking Dogs Never Bite. The shifts (and the themes) are very much what Bong Joon-ho will later revisit and expand upon in Parasite, but personally I feel that a lot of the awkwardness and discomfort works better in that earlier, much more lo-fi effort. It’s clear even from his student films that the director loves playing with our expectations, ambushing the viewer with deliberate incongruity, and if the early stuff has very clear jumps, Parasite works out the shifts in subtler ways, without compromising on the surprise and shock value.

I recently started watching the Scottish sitcom Still Game, and was struck by a rather weird sequence—the two protagonists walk into the pub, the landlord tells one of them has gained weight, to which he replies: every time I shag your wife she makes me a sandwich. Then they realize the pub is running sweepstakes on who among the neighborhood elderly is going to die from hypothermia. We go from a tired cozy joke to something quite harrowing within one scene. It’s not important whether this particular tonal shift is a mistake, or a deliberate choice, not even whether it works or not—the strangeness of it made me remember the episode more vividly than anything else in the show, and it’s worth noting that the scenario would probably feel a little less cruel if it weren’t preceded by such a vanilla opening.

Of course cruelty and incongruity should ultimately feel satisfying. It’s the difference between being a victim of a practical joke that makes you feel delighted, and one that makes you feel exploited. The ideal scenario is sneaking up on the reader and giving them something that didn’t expect, but, on reflection, do want. Stewart Lee has always played with antagonizing his audience, and it’s worth looking for bootlegs of his shows-in-progress—you realize how subtle and complex this act can be, and how a seemingly similar routine can turn from vague aggression to a full narrative. As he gained popularity, the audience started catching on and expecting him to be confrontational, and he’d attempt to confront that and attack the audiences for liking his confrontations.

It’s a risky business—cruelty can ring hollow, if it doesn’t feel earned and justified, either by the story, or by a setting that’s absurd enough to absorb it. The latter is fairly clear—it’s the foundation of all the classical cartoon violence and theater (the creators of Bottom devised the show while working on a production of a Beckett play, and White Lotus, despite its realism, presents the cast within the flattish framework of genre fiction). The story route is more fraught, and requires more risks and more planning.

A lot of it, I think, is a matter of building trust, and that takes time and work. To examine a build-up towards cruelty, let’s look the famous Holiday episode of Peep Show. To save you from spoilers, I will begin and end the following section with large photos of happy dogs. If you haven’t seen Peep Show, wait for the second large happy dog, and you can start reading again.

SPOILERS AHEAD

SPOILERS AHEAD

SPOILERS AHEAD

SPOILERS AHEAD

SPOILERS AHEAD

SPOILERS AHEAD

There are lots of notably cruel Peep Show episodes, but I’m picking this one because it’s very divisive among fans, and I think it’s more interesting to examine something that isn’t a universal hit.

The episode starts with Mark’s rant about data entering, then Jez talks him into going on a boat trip. All normal stuff. The first minutes of the episode lull us into a familiar territory, even if we hadn’t seen any episodes of the show—there’s the dull character, and the erratic character, and we know what to expect from their personality clash for the next 20-something minutes.

The boat trip doesn’t start yet—first we have a therapy session with Mark and his fiancé, Sophie. Mark is initially excited about it, he thinks he’ll get out of his marital obligations, but the session immediately derails into a beating for Mark. The character writing is perfect—Mark’s avoidant fury, Sophie’s repressed dissatisfaction. The therapist is barely there as a character, very flat—her only role is to buffer the other two, and it’s a nice show of restraint on the writers’ part—so often every single background character gets padded with personality for no good reason.

Then the boat. The therapy session primed us on Mark’s relationship—if we aren’t familiar already, we know he’s dying to get away and clearly doesn’t believe that any amount of therapy can fix things. Jez immediately gets bored of his own boat trip idea, which is good characterization—of course he didn’t think it through beyond the gesture. Chris Morris said somewhere that Peep Show is a perfect dissection of male insecurities, and here they are displayed from every angle. I remember telling a friend that every man is a mix of Mark, Jez and Super Hans, and I’m probably 60% Mark, 25% Jez and 15% Super Hans, and she said this breakdown makes you a 100% Mark.

The tension between Mark and Jez escalate as they struggle to have anything to say to each other. It’s clear that their camaraderie is mainly sustained by mutual endurance at this point. Jez gets so bored that he offers to drink Mark’s piss, for a laugh. It’s a ridiculous thing to suggest, but within the realm of the sort of dumb thing lads might suggest on a stag do (spoken as a person who’s never been invited to anything of the sort). Still, it reinforces Jez’s impulsivity and willingness to cross the line.

Finally, Jez drags Mark to a pub, and immediately starts hitting on a couple of women having their dinner. The sisters, Aurora and Lucy, have some light dialogue, but Lucy takes an opportunity to have a bit of a dig at a charity man that talked to them earlier. Normally that kind of characterization can feel very ‘written,’ but here it sneaks in with a nonessential bit of dialogue. Mark makes a genuinely good joke about a interdenominational hangover, but no one laughs at it and he doesn’t even get to finish the sentence—again, good restraint.

We move to the sisters’ boat, or their dad’s, as they inform the lads. The time shift feels natural—we start with a stretch of boredom earlier, then, as they enter the pub, things accelerate, which is how it would feel in our memories, had we gone through the same sequence of events. No needless scene transitions and extra fluff. And we finally meet the dog, Mummy. Aurora, the more conventionally attractive sister that Jez fancies, reveals her neuroses, as she aggressively pets the dog and calls her “naughty, slutty Mummy” for having lots of puppies.

She also reveals that their mother is dead, another ingredient in the brewing cruelty stew. Lucy immediately asks Mark if he has a girlfriend, and he shows his snaky side by answering “not really.” We get a quick mention of Pej, the mysterious classmate of Mark and Jez’s that gets alluded to in a few episodes, a bit like Bob Sakamoto in Seinfeld. A truly inexhaustible comedic invention—every sitcom should have its Pej to take the burden of the more outlandish anecdotes.

Then their dad arrives, and we move straight into Mark’s morning hangover—another time skip. It would make sense for us to meet the dad, but we get to meet him in a bit anyway, and removing that sequence leaves us a bit of intrigue. It might of course be the matter of editing to fit the episode format. As is, the transition is a bit odd, but things move fast, and we don’t feel like we’re missing much. Plus, they are now hungover, which gives the shaky time skips more plausibility.

The four of them are having lunch with the dad. Jez hits on Aurora, and is given the keys to their 4x4 for a shopping run. At this point it’s pretty clear that the family is well off, and, knowing Mark (remember his frustration with work in the very beginning), we can expect him to have a bit of interest in Lucy, now that she presents him with an opportunity to get an easy job. Mark immediately goes into his sheepish mode which he reserves for older men in positions of authority or power, especially if there’s a chance of him leeching onto said positions.

Mark starts going on about his expertise while Lucy grabs his knee, and Mark thinks: this is like that dream I had of Alan Sugar and the Badger. A brilliant brit of absurdity in the middle of a character scene, except that apparently it’s a reference to an actual person on the Apprentice, called Ruth Badger… I much preferred the joke when it was just a badger in my head—oh blast research! Animal or human, it’s great that he says “Alan Sugar and the Badger—no extra sex jokes piled on top. We don’t know what the thruple between Mark, Alan Sugar and the Badger might look like, and that only makes it funnier.

Meanwhile, Jez drives Aurora to the grocery store, kisses her for the first time, goes through his usual mental confusion between love, lust and boredom, and, having quickly established that he’s drunk, stoned, and a bit high from his latest conquest, runs over Mummy. Everything happens very fast, which feels realistic—it’s the sort of mistake one can imagine making, which adds to the horror. The crunch of the bones and the whimper suddenly bring us into the dark side side of the episode, about 2/3 way in.

This is where things get complicated, because now it’s time for Jez to show his awful side as he attempts to get away with murdering the dog, and tells Aurora that Mummy has probably run off. He’s carrying the dog in his bag, which is idiotic, but believable enough, because Jez is established as a bit of an idiot, plus he is stoned, drunk, and in shock. They start shouting for Mummy, and the sound of the dog’s name becomes even stranger—Aurora is clearly unstable, and the though of losing another Mummy makes her even more neurotic.

Mark is still ingratiating himself with the dad, while Lucy rolls her eyes at the message from one of her friends who’s talking about committing suicide. It’s worth noting that the two sisters have a similar level of near-flatness—there’s enough characterization to make them believable, but not enough to make us deeply invested in their lives, while the father is even flatter, just a narrative device to keep Mark sticking around.

We’re back in the stag boat. Mark excitedly tell Jez about his job opportunity, which doubles as a chances to escape the impending marriage to Sophie, and Jez reacts in a manner more stunted than usual. He gets scared of Mark leaving—he’s clearly unstable, though still keeping up his chatty appearances. Mark opens the bin and sees the dog. Jeremy, he says, is this… Mummy? The name continues to be milked, with increasing levels of cruelty.

Jez tells him that if they can get rid of the dog corpse, he might still get laid. Now, here’s where this episode goes quite a bit wild, and why some people see it as a misstep in the series. Jez is selfish and dumb, but he’s not a total psychopath. This episode, however, pushes his character really far, and whether it’s justified or not is subjective, but let’s keep looking at the mechanics of the story. However extreme it is, the escalation is well-paced and gradual—we have Jez’s mounting frustration, the time he invested in seducing Aurora, and most importantly, the rising absurdity of the situation, which drags the absurdity of the characters’ actions along with it. Mummy’s name is great help here, too. It is at once upsetting and ridiculous, a rare combination.

They go into the woods and try to burn the dog, and the dog doesn’t burn well because Mark didn’t want to buy firelighters. The fire goes out, and they try to bury the dog, but there’s nothing to dig with. More time passes—Jez has failed to bury the dog, so he just carries it in a plastic bag. Stupid, but at this point we’re approaching the height of escalation and realism doesn’t matter much, we just want to see this to the end and accept anything coming our way. He expects to dump the dog, but runs into Aurora. She invites him back to the boat, and he can’t help but follow his horn. The viewers have certainly acclimatized to the rhythm of the escalation by this point—they are afraid of what’s coming up, yet can’t look away.

Back on the boat, Mark is finishing his interview with the dad, and we have a brief respite of regular humor before the shocking finale. Jez and Aurora get in, and Mark looks mortified at the sight of the bag, which Jez holds tightly on his lap. Lucy, easily distracted, asks what’s in the bag, and Jez tells them it’s barbecue. Things move on fast—Aurora grabs the bag and takes out a half-burned leg of her beloved dog. Jez takes the leg from her, and takes a bite to prove that it’s turkey. The speed of it all is crucial—more deliberation would make the horror sink in, instead we just move on deeper and deeper, until Aurora fishes out the nametag and says: they ate Mummy!

What happens next is curious—Mark says he’ll email the resume, and Jez, while licking his finger, tells Aurora he’ll call. This is horrifically cruel, and way out of character for both of them. That said, we are surfing on the high of Jeremy eating an partially burned/buried dog, so these lines sneak in under that giant shockwave.

Walking off, Mark asks if he really needed to eat it, and Jez says I don’t know, I keep wondering that, but you know, in the moment it really felt like I needed to eat it. Mark nods in confusion, and that’s it, credits. The closing lines are much less bombastic than the previous ones, acting as a parachute from the above-mentioned wave. People say that you should end on a high note, but with a transgression like this one, it makes sense to wrap it up quietly.

Now, I don’t know how I feel about this episode myself. I remember loving it on the first run, and loving the shock and disgust that it instilled in me—I’m not easily offended by fiction, and the thrill of escalation justified everything. That said, I understand when people say the writers have gone too far—Jez’s psychopathic responses towards the end are way too outlandish to be believable, even with the escalating absurdity. Personally, I find Aurora’s fragile mental state to be the most questionable part, but if she were written flatter, the ending wouldn’t have hit as hard. However you feel, the episode is a great example of planning—Jez is carefully eased into dog-eating, and however believable that is, the whole thing is a notable achievement.

Perhaps it could’ve ended like this: Jez bites into the dog and snaps into reality as Aurora reads the nametag. Then, instead of quipping, he just staggers off along the shore, his dog-handling hand shaking, while Mark gets off the boat and stands confused and indecisive, his eyes dart between the crying family and the retreating Jez. I would’ve probably gone for that—you’ve done total escalation, so why not top it with a total tone shift? I think it would be nice to bring it back to Earth and allow things to sink in, instead of letting Mark and Jez get away with it. I think that’s another thing that feels off—most of the show, Mark and Jez are the ones getting tortured, and it’s odd to see them relatively composed after this incident.

Either way, I’m glad they went there—it’s rare to have such a deranged storyline to pick apart. But what do you think of the episode? Let me know, I’m always curious to hear—some people see it as a highlight, others go as far as skipping it on their reruns.

SPOILERS END

SPOILERS END

SPOILERS END

SPOILERS END

SPOILERS END

SPOILERS END

In Succession, Jesse Armstrong, one of Peep Show’s co-creators, explores cruelty further, especially in the relationship between Tom and Shiv, not to mention Ken’s birthday party, or Boar on the Floor. In that show, however, all the sadism is grounded in realism and drama, and never rises to the Mummy level. When truly horrible things do happen, the characters struggle to hold on to their cynical foundations, and it creates a whole different level of drama when a wisecracking asshole like Roman wrestles with his emotions. It’s a more mature writer exploring the same themes, delving deeper than ever, but carefully constructing a believable world that allows for a slow build-up and a more emotional kind of torture. Still, the impulse is the same, I think—putting characters into an uncomfortable situation and seeing how far things can go. By the way, did you notice the sucky-fucky inversion in the last episode?

FINALLY, CONSIDER THIS

If everyone suffers, is it still cruel? Yes, but it probably feels less cruel than a scenario where some characters suffer disproportionately more than others. When everyone suffers, it creates a kind of low-level hell that can be comforting and even charming. I’ve instinctively applied this principle to myself, or so I’ve been told by many people—my pessimism is so pervasive and over-the-top, that it can be entertaining (although that also means that when you really are in crisis, no one takes you seriously). Now, my goal is to channel that negativity into my work and write stories that burrow into the darkest recesses of human discomfort and look for humor there. Stay tuned—the essays will soon end, and proper comics will continue. I was in quite a rut for years now, hence all the blender business and whatnot, but lately I feel like I finally rediscovered my love of cartooning, in other people’s work as well as my own, and now all I want is to draw funny stories forever.

PS. I’m traveling to the UK first ten days of May, mostly London/Wales. Probably will be fairly busy, but feel free to reach out!